Easy Sourdough Bread (Whole Wheat-ish)

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read my disclosure policy.

This is my favorite sourdough bread: It’s high hydration, whole wheat(ish), and just so darn tasty. As far as sourdough recipes go, this is about as simple as it gets. Below, you’ll find video guidance for every step of the process. Let’s do this! 🍞🍞🍞🍞

Sourdough is often described as a journey. The more I make it, the more this sentiment becomes a truth. For the past few years, I’ve been tinkering with various sourdough recipes, and though I can’t say I won’t stop tinkering, this is the current snapshot of my sourdough journey.

These are the characteristics I like in a sourdough boule:

- high hydration (at least 75%)

- whole wheat-ish

- crusty but not super crusty

- nicely salted

- tangy though not super sour

I’ve outlined the process below to create this type of loaf, which as far as sourdough recipes go, is on the simple side — there’s no kneading, no autolyse-ing, no pre-fermenting, no levain-ing, no fancy scoring.

It’s a little bit smaller than most sourdough boules, too, reasons for which I explain below. And as with all sourdough baking (and bread baking in general), it does take time, though the time is mostly hands off.

This post is organized as follows:

- Two Sourdough Fermentation FAQs

- Two Tips for Assessing Fermentation

- Whole Wheat Flour

- Roller-Milled vs. Stone-Milled Flour

- 75% Hydration

- Mixing Sourdough Bread

- Bulk Fermentation

- Shaping + Bench Rest

- Proofing Sourdough

- Scoring and Baking Sourdough

- The Best Way to Store Bread

2 Sourdough Fermentation FAQs

Two of the most frequently asked questions I receive about sourdough bread baking are:

- How do I know when the dough has risen sufficiently and is therefore ready to be shaped?

- How do I know if it has proofed sufficiently and is therefore ready to be baked?

If you are unfamiliar with sourdough baking, these two questions relate to two distinct phases of fermentation:

- The first question relates to the bulk fermentation (the first rise), which takes place after the dough is mixed.

- The second question relates to proofing (the second rise), after the dough is shaped.

One thing I have learned through troubleshooting with various people is that it’s very hard to put a timeline on these two phases. Sourdough is much more sensitive than yeast-leavened breads to the environment in which it is being baked.

The bulk fermentation for me in my cold Upstate New York kitchen often takes 12 hours regardless of the time of year. For someone baking in humid Hawaii, it may take 6 hours (or less! or more!). Similarly, the proofing phase may vary by many hours depending on the environment. Additionally, there are countless variables that affect fermentation: type of flour, water, salt quantity, strength of the starter, to name a few.

Yes, there are textural/visual cues to help discern when each phase of fermentation is complete, but it still can be hard to judge.

If you struggle with these assessments, I have two tips for you:

2 Tips for Assessing Sourdough Fermentation

Tip #1: Buy a clear, straight-sided vessel.

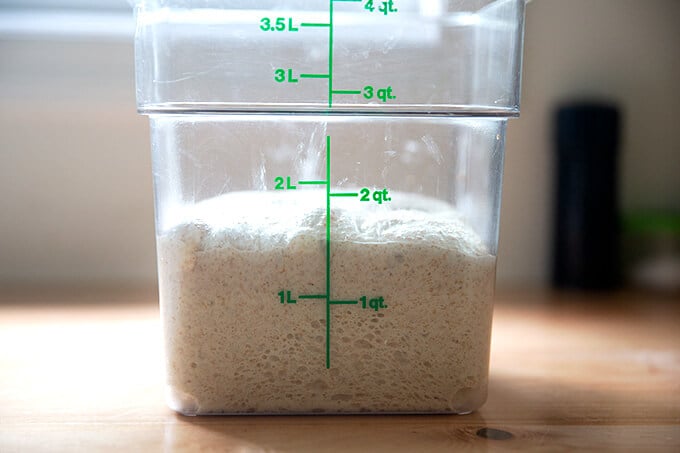

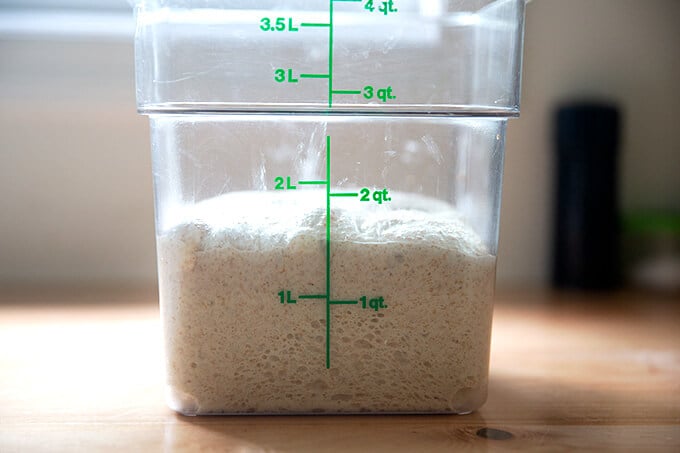

After my digital scale, my clear, straight-sided 4-qt Cambro (**this one is BPA-free!**) has become my most important tool when it comes to sourdough bread baking. Why? For two reasons:

- Because it’s clear, it allows me to see when the dough is filled with bubbles and activity throughout — top, bottom, sides, etc.

- Because it’s straight sided, I know exactly when the dough has risen sufficiently (roughly 50% increase in volume) and is therefore ready to be shaped. When dough rises in a bowl, it’s very hard to gauge how much the dough has grown.

If I could single out the biggest lesson I’ve learned in my sourdough baking journey, it’s this: Do not allow sourdough rise beyond double during the bulk fermentation.

Why? When sourdoughs rise for too long, the dough weakens. A weak, fragile dough is hard to handle and difficult to shape into a tight round, which in turn makes for a dense loaf. Most recently I shoot to shape the dough when it has increased by 50% in volume.

Tip #2. Use Your Refrigerator & Be Flexible

Because judging bulk fermentation and proofing can be tricky, you can use your refrigerator during both phases.

Using your fridge for the bulk fermentation:

If, for instance, you see your dough rising nicely but all of a sudden it’s 10 pm and you’re ready for bed, and you know if you let the dough continue to rise, it will be way beyond double in the morning, stick the vessel in the fridge. The following morning, take it out and let the dough rise at room temperature until it has nearly doubled or, as I advise more and more, increased by 50% in volume.

With sourdough baking, you have to be patient, and you have to be flexible with the timing.

Using your fridge for proofing:

Using my fridge for the proofing phase has been the biggest change in my sourdough process of late. Previously, after shaping the boule and placing it in a towel-lined bowl, I would transfer the dough to the fridge for 1 hour, then bake it. These days, I like to stick the shaped boule in the fridge for at least 12 hours, but ideally 18-24 hours. Why?

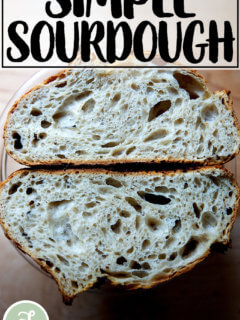

- The extended cold proof creates a lighter, airier crumb.

- A cold round of dough is so much easier to handle from scoring it to transferring it to the Dutch oven.

Whole Wheat Flour FAQ

In my email course, Foolproof Bread Baking, I receive a lot of questions about how to incorporate more whole grain flours into bread.

This is a tricky one to answer for me for two reasons:

- I like white bread. A good loaf of bread for me has so much to do with texture. I love a pillowy, oily focaccia; a soft, squishy brioche bun; a ballooned, crisp-tender Neapolitan pizza. As soon as whole grain flour is entered into the mix, the texture changes, becoming heavier, denser.

- Commercial whole wheat flour isn’t necessarily healthier than commercial white flour. Wait, what? Read on.

Roller-milled Flour vs. Stone-milled Flour

Without getting too far into the weeds, most of the commercial flour on the market is made from wheat that has been roller milled, meaning a roller mill has separated the wheat kernel into three parts: the endosperm, germ, and bran. White flour is made from the endosperm.

Whole wheat flour, similarly, is made from rolled-milled wheat: again, first the kernel is separated into three parts: the endosperm, germ, and bran; BUT then the germ and the bran are added back in various proportions. Much research shows that as soon as the wheat kernel is separated into the various parts, much of the nutritional value is lost — even when the bran and germ are added in after the fact.

So what’s the solution?

Stone-Milled Flour

Stone-milled flour, contrary to roller-milled flour, is flour made from wheat that passes through a stone mill, the process of which keeps the endosperm, bran, and germ together. Much research shows that keeping the components together preserves the nutritional value.

The rub with stone-milled flour? Stone-milled flour is more perishable due to the presence of both the bran and the germ, but the germ in particular, which is packed with vitamins, minerals, and fats, which can go rancid quickly.

The boon? Because the bran and germ are present in the flour, it’s also more flavorful.

Anything else to consider? Baking with stone-milled flours requires a little more finesse. Even a small amount of bran and germ in the mix makes for a denser loaf. Many millers offer high-extraction stone-milled flours — meaning stone-milled flours that have been sifted to remove some of the bran and endosperm. But even when you bake with high-extraction, stone-milled flour, the finished loaf, when made from 100% of this type of flour, will be very dense.

For this reason, I use at the most 25% stone-milled flour (100 g for this recipe), but preferably in terms of texture, 12.5% stone-milled flour (50 g for this recipe). 12.5% may seem like a tiny amount, but I am constantly surprised by how much flavor, texture, and color this small proportion of stone-milled flour offers to a loaf of bread.

In fact, I now prefer a partially whole wheat loaf to an all white loaf. The freshly milled, stone-milled flours offer so much flavor.

Where to Buy Stone-Milled Flour?

In the past few years, it has become easier to find stone-milled flour, and if you are up for it, you should seek out locally, stone-milled flour. Why? Because if you’re buying locally milled flour, you likely can find out how recently it was milled. Because stone-milled flour perishes more quickly than roller-milled flour, it’s best if you can find a local source, which will ensure it will be fresh. Note: Store stone-milled flour in the freezer if you don’t bake regularly.

Final note: I no longer buy commercial whole wheat flours. I buy commercial white flours: King Arthur Flour’s all-purpose flour and bread flour are staples. I find locally milled stone-milled flours at a local co-op, Honest Weight Food Co-op, and I also order online from various sources. Here are a few I love:

Finally: Here’s a great resource if you’re interested in learning more about wheat and flour: The Bread Lab. Also, Dan Barber’s The Third Plate was eye opening.

75% Hydration

Standard sourdough recipes often call for 500g of flour per loaf. As noted above, the recipe below makes a loaf that’s a little bit smaller for two reasons:

- I’m often asked if the bread recipes here on the blog as well as in my book can be halved. The answer is yes, but in an effort to make a loaf that may not feel quite so overwhelming for people, I’ve reduced the flour to 400g.

- I wanted to include quantities that make hydration easier to understand. Hydration is something I don’t discuss too often because I find it can turn people off (me included). In short, hydration is: the ratio of water relative to flour in a bread dough. The proportions in this recipe — 300g water and 400g flour — make it a little easier to see it’s a 75% hydration dough: 300/400=0.75.* With this baseline, you can increase the amount of water to make it higher hydration or decrease the amount of water to make it lower hydration depending on your preference.

*Note: This is a crude calculation. If you want to be super accurate when calculating hydration, you include the weight of the starter in the equation, too, which will throw off the percentage slightly.

Salt

I love salt. The standard percentage of salt in a bread recipe is 2% by weight of the flour. For 400g flour, this means 8g salt. I use 10g. The amount of salt, fortunately, is a variable that can easily be tailored to your liking. If 10g of salt is too much for you or if you know from the start you are sensitive to salt, start with 8g, then adjust accordingly. Also, higher amounts of salt will slow down the rise a bit as well.

5 Phases: Simple Sourdough Bread

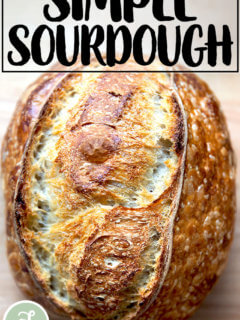

This videos and photos below shows how to make from start to finish the high-hydration, whole wheat(-ish) sourdough bread recipe included at the end of the post.

Phase 1: Mix the Dough

Step 1: Gather your ingredients — flour, salt, water, a sourdough starter — and equipment, namely a digital scale. I recommend buying a starter (reasons for which I explain here). But if you’re up for it, you can make a sourdough starter from scratch in just about a week. I only recommend doing so if it currently is summer (or a very warm fall) where you are.

Most important, you need a fed, active starter.

To ensure it is ready, drop a spoonful of it in a glass of water. If it floats, it’s ready:

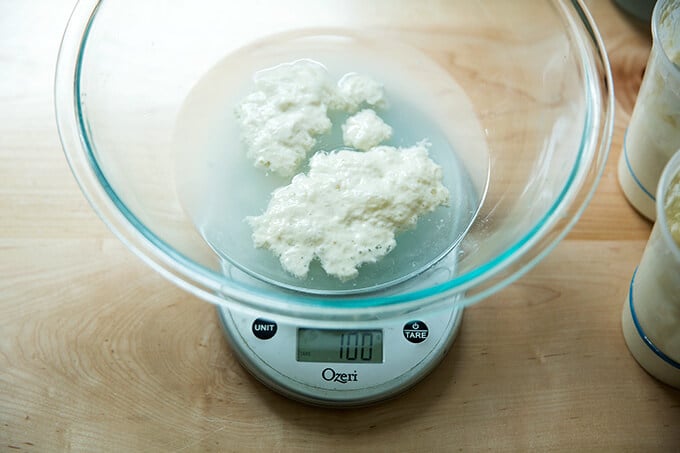

Start by weighing 300g water, 100g starter, and 10g salt.

You’ll need 400g flour. You can use all bread flour of a mix of bread flour and whole wheat flour. My preferences is 350g bread flour (King Arthur Flour) and 50g stone-milled, freshly milled flour (I use a mix of Anson Mills rye and graham).

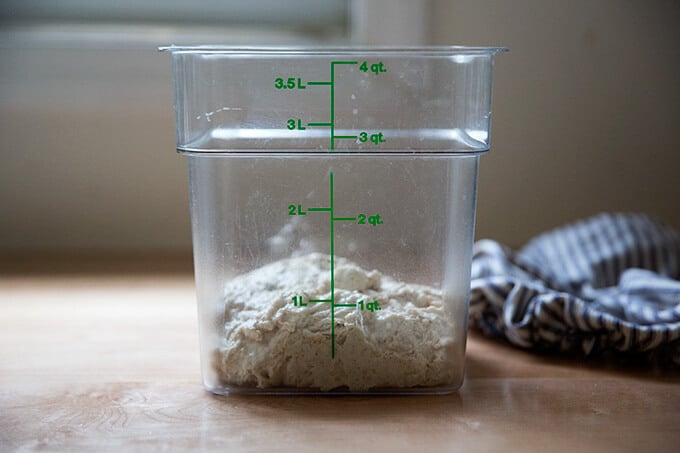

Mix to form a sticky dough ball.

Then transfer to a straight-sided vessel for the bulk fermentation (the first rise).

Phase 2: Bulk Fermentation

After 30 minutes, stretch and fold the dough:

You’ll repeat this stretching and folding 3x at 30-minute intervals; then you’ll leave the dough to rise until it increases in volume by 50-75%.

Phase 3: Shape + Bench Rest

Transfer dough to a clean work surface. I prefer to use no flour and minimal handling to shape it into a ball.

After the initial shape, let the dough rest for 20-40 minutes; then shape again and transfer to a flour sack-lined bowl.

Phase 4: Proof

Transfer bowl to fridge to proof (second rise) for 18 to 24 hours

Phase 5: Score + Bake

After 18 to 24 hours, transfer dough to a sheet of parchment paper. This video shows how:

Score as you wish; simple is fine.

Transfer to a Dutch oven and bake at 450ºF covered for 30 minutes, then uncovered for 10 minutes at 400ºF.

The Best Way to Store Bread

How do I store bread? is one of the most frequently asked questions I receive.

If you want to store the bread at room temperature for 3 to 4 days, I think the best method is in a ziplock bag. I’ve tried other reusable/environmentally friendly options, but nothing seems to keep bread freshest — the crumb the softest — better than a ziplock bag.

If you intend to keep the bread for longer, I would stick the ziplock bag in the freezer, and pull out slices or hunks as you wish. I often slice bread as soon as it cools completely, transfer the slices to a ziplock bag, then freeze. This way, I know the bread was frozen at its freshest.

A ziplock bag will not prevent the crust of bread from turning soft, which is why I suggest always reheating day-old bread. I use a toaster at breakfast for slices of bread, and I reheat half or quarter loaves in the oven at 350ºF for 15 to 20 minutes when serving for dinner.

Bread revives so beautifully in the oven or toaster.

I baked this loaf in a tall-sided pullman loaf. Love the shape! I proofed this in the fridge for about 12 hours; then let rise at room temperature for roughly 5-6 hours before baking at 400ºF for about 40 minutes.

Easy Sourdough Bread (Whole Wheat-ish)

- Total Time: 48 hours 45 minutes

- Yield: 1 loaf

Description

Special equipment: Straight-sided vessel for the bulk fermentation, Dutch oven, flour-sack towel

Here’s my list of essentials for sourdough bread baking.

Digital Scale: Do not attempt this recipe without a scale. This one costs $9. Troubleshooting what goes wrong with sourdough bread is impossible if you’ve measured with cups. They’re simply not accurate.

Troubleshooting: If you have issues with your dough being too sticky, please read this post: Why is my sourdough so sticky? The 4 common mistakes.

Flour:

- I prefer making this bread with 350g bread flour and 50g of freshly milled, stone-milled flour, which provides both flavor and color. (Read the post above for more details and why I suggest stone-milled flour as opposed to commercial whole wheat flour.) I’ve been using a mix of Anson Mills graham flour and rye flour, but there are many great stone-milled flours out there, and you may have a local source, which is even better.

- 50g may seem like a tiny amount of stone-milled flour for this recipe, but I am constantly amazed by how much flavor this small amount of freshly milled flour adds. If you are new to sourdough baking, I recommend starting with 100% bread flour (King Arthur Flour is my preference) because it’s so forgiving and easy to work with. Once you get the hang of it, start incorporating stone-milled flour a little bit at a time. I don’t like using more than 100g (25%) of stone-milled flour in this recipe.

- If you cannot find bread flour — I know supplies are limited at the moment — you can use all-purpose flour. If you live in a humid climate, consider reducing the water by 20 g. You can add the 20 g of water in slowly while you mix until the dough resembles that in the video/photos.

Salt:

I like breads to be a little bit saltier than standard. If you are sensitive to salt, start with 8g. Next time, adjust salt as you wish.

Ingredients

*Please read notes above before proceeding. Watching the video is helpful, too.*

- 400 g bread flour, see notes above

- 8g to 10g kosher salt or sea salt, see notes above

- 300 g water

- 100 g active sourdough starter

- rice flour, for dusting

Instructions

- Mix the dough. In a large bowl, combine the water, starter, and salt. Stir with a rubber spatula to loosely combine. Add the flour, and stir with a spatula to combine — it will be a wet, sticky dough ball. Transfer to a straight-sided vessel and cover with a tea towel or bowl cover for 30 minutes.

- Stretch and fold. After 30 minutes, grab a corner of the dough and pull it up and into the center. Repeat until you’ve performed this series of folds 4 to 5 times with the dough. Let dough rest for another 30 minutes and repeat the stretching and folding action. If you have the time: do this twice more for a total of 4 times in 2 hours. [Video guidance here.] Note: Even if you can only perform one series of stretches and folds, your dough will benefit. So don’t worry if you have to run off shortly after you mix the dough.

- Bulk fermentation: Cover the vessel with a tea towel or bowl cover and let rise at room temperature (70ºF/21ºC) for 4 to 18 hours (times will vary based on the time of year, the humidity, and the temperature of your kitchen). The bulk fermentation will end when the dough has nearly doubled in volume and you can see bubbles throughout the dough and on the surface. (Note: Do not use your oven with the light on for the bulk fermentation — it is too warm for the dough. To determine when the bulk fermentation is done, it is best to rely on visual cues (doubling in volume) as opposed to time. A straight-sided vessel makes monitoring the bulk fermentation especially easy because it allows you to see when your dough has truly doubled.)

- Shape: Gently transfer the dough to clean work surface. I prefer to use no flour and a bench scraper at this step, but if you find an un-floured work surface to be difficult, feel free to lightly flour it. [Video guidance is especially helpful for this step.] Fold the dough, envelope style: top third over to the center; bottom third up and over to the center. Then repeat from right to left. Turn the dough over and use your bench scraper to push the dough up, then back towards you to create a tight ball. Repeat this pushing and pulling till you feel you have some tension in your ball. Place the dough ball top side down and let rest 30 to 40 minutes. (FYI: This is called the bench rest.)

- Proof. Line a shallow 2-qt bowl (or something similar) with a tea towel or flour sack towel. Flour sack towels are amazing because the dough doesn’t stick to them, and therefore you need very little rice flour, but if you only have a tea towel, you will be fine. If you are using a tea towel, sprinkle it generously with rice flour. If you are using a flour sack towel, you can use a lighter hand with the rice flour. After the 30-to 40-minute bench rest, repeat the envelope-style folding and the bench scraper pushing and pulling till you have a tight ball. [Video guidance here.] Place the ball top side down in your prepared towel-lined bowl. Cover bowl with overhanging towel. Transfer bowl to the fridge for 12 to 24 hours. (Note: When you remove your dough from the fridge, visually it will likely look unchanged. This is OK. You do not need to let it then proof at room temperature before baking.)

- Bake. Heat oven to 500ºF. Remove your sourdough from the fridge. Open the towel. Place a sheet of parchment over the bowl. Place a plate over the parchment. With a hand firmly on the plate and one on the bowl, turn the dough out onto the parchment-paper lined plate. [Video guidance here.] Carefully remove the bowl and towel. Carefully remove the plate. Brush off any excess rice flour. Use a razor blade to score the dough as you wish. I always do a simple X. Grab the ends of the parchment paper and transfer to the Dutch oven. [Video guidance here.] Cover it. Lower oven temperature to 450ºF, bake covered for 30 minutes. Uncover. Lower temperature to 400ºF. Bake for 10 minutes more or until the loaf has darkened to your liking. Transfer loaf to a cooling rack.

- Cool. Let loaf cool for at least 30 minutes before cutting.

- Prep Time: 48 hours

- Cook Time: 45 minutes

- Category: Bread

- Method: Sourdough

- Cuisine: Global

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read my disclosure policy.

987 Comments on “Easy Sourdough Bread (Whole Wheat-ish)”

Hi!

Can I add nuts to this recipe?

Yes! Add them with the flour. I would start with 3/4 to 1 cup; next time around, adjust based on your results.

Hello! I just wanted to say that I was struggling with this dough being sticky, floppy, and totally unshapeable. I mixed it, stretched + folded, bulk fermented until 50% increased in size, turned it out onto a countertop, and it was a puddle of dough, even at 1/8 whole wheat. The loaves tasted great, but very flat shape.

Then I took a look at your helpful comment replies, and I realised I was indeed using all-purpose flour instead of bread flour. I read your suggestion to use less water, so I reduced water by 50g and kept everything the same. This morning I have a beautiful crusty loaf that was a pleasure to work with at every step of the process. Absolutely thrilled.

Thank you for your writing style, it really makes the whole process very enjoyable to read, all the way from first read to many subsequent references.

Hi Bashu!

Thanks so much for all of this. I am constantly amazed by the importance of the details with sourdough … it’s just not as forgiving as yeast-leavened breads, and small changes can make a huge difference. I’m so, so glad you were able to adjust the recipe and get great results. Thank you for writing!

Hi Ali,

Did your mentioned your also baked this in a loaf pan??? 😱

Yes! It worked beautifully!

Hi Ali,

I tried all 4 of your sourdough recipes (sourdough focaccia, sourdough toasting or sandwich, simple sourdough and whole wheat-ish) and all of them are amazingly delicious. I will be making them on a rotation weekly.

Can I just use this recipe for all 4? I like how this flour portion is smaller and with some whole grain flour. Thanks!

Hi Angela! So nice to hear this. The hydration of this one and the simple sourdough are basically the same … I prefer this one as well for its smaller size.

The focaccia and toasting bread are a little bit higher hydration, so if you wanted to make each of those using 400 g flour, you might want to increase the water to 335 g. Hope that makes sense!

yes!!

What is the highest amount of freshly milled wheat flour do you recommend for this? 100g? Thanks!!!

Hi Angela! Yes, I wouldn’t do more than that… I might even start with 50 grams … but if you’re OK working with a stickier dough, then go with 100 grams.

Hello! I had to put my dough in the fridge as it wasn’t quite finished at bed time…..I’ve pulled it out this morning and it’s doubled….do I need to wait for it to warm up to room temp before shaping? Or can I do this straight from the fridge? And also, because it spent all night in the fridge, do I need to do the second rise in the fridge? If not how long do I leave it on the bench? Thanks! Made this bread lots and it’s delicious!

Hi Carlee! Sorry for the delay here. No need to let it come to room temperature: simply get it out onto a work surface for the bench rest. Funny, I had the same scenario happen to me last night/this morning, so this morning, I turned out the cold dough onto my work surface and let it rest for 45 minutes. I only did one shaping; then stuck it back in the fridge. I won’t bake it till tomorrow. I do think doing the second rise in the fridge is important especially if you want to achieve a light crumb.

Hope that helps! Let me know if I’ve answered your questions or if you have more questions.

My oven has been out of commission. So I’ve lost my old recipes (even on the computer) So glad I found this old favorite by Googling wheatish! And the answer to the question about overnight bulk rise in fridge and then immediate bench rest and proofing loaves (I double) in fridge was exactly what I needed. Were the good spirits watching over me? The whole article and the real life directions are the best tune a baker could get. Attitude is everything. Thank you so much.

So wonderful to hear this, Susan! Glad your oven is back in commission. Happy Baking!

Hi Alexandra,

When you baked this one in a loaf pan, did you use a covered loaf pan?

Thanks

Swati

Hi! Nope, not covered. Though someone messaged me recently telling me he had baked the sourdough sandwich bread in a covered Pullman loaf, and it worked beautifully. I’m eager to try!

Thanks… I baked it open and it was beautiful except that like a cake I left it for an hour in the pan after taking it out of the oven and the sides had condensation on them but it is still great. Thanks for making our family sourdough addicts.

So nice to hear this, Swati! Bummer about the condensation, but glad it didn’t ruin the loaf.

This bread has been my best yet for rise & flavor. I may have overproofed my previous loaves.

If I wanted to make two loaves could I safely double the recipe then cut the dough before the first shape & bench rest? Or would it be better to just make 2 separate batches ?

Wonderful to hear this, Renata! And yes, absolutely, doubling it works great.

Because of health issues I need to use whole wheat flour exclusively for the recipe.

What changes should I consider as a result of this? Do you have a better recipe of only WW flour?

Hi Christi! I think this is the kind of thing you are going to have to experiment with. A loaf made with 100% whole wheat flour is going to be on the dense side, which is fine, but just manage your expectations going into it. Also, because all whole wheat flours absorb water differently, I can’t really advise on how to adjust the water. I would make the recipe as is using your flour. Reference the video to see what the texture of the dough should look like. Add water as necessary to achieve the right consistency. Use a scale, even when adding the additional water, so you have an accurate figure to reference moving forward.

Out of curiosity, what brand or type of whole wheat flour are you planning on using?

First attempt was a major success. Thank you so much

Wonderful to hear this, Nicole! Thanks so much for writing 🍞🍞🍞🍞🍞🍞

I just wanted to thank you for this wonderful recipe!

My homemade sourdough has never turned out this good!!! I’ve baked it today and I’m currently starting another batch!

A few days back I’ve also made your focaccia. A W E S O M E as well, but I’m sure you already know that, haha!

I’m Italian AND a blogger myself, I’ve always nailed focaccia with instant yeast (I actually have a recipe on my blog if you’d like to take a look) but I was never happy with the outcome of the ones with sourdough starter….until I discovered your gorgeous blog!

The only shame is that I’ve discovered it just now!

Take care and keep up the amazing work 🙂

Adriana Z.

So nice to hear all of this Adriana! Thanks for writing 🙂 🙂 🙂 And I’ll definitely check out your focaccia recipe!

Hello

Do you have a general breakdown of the nutritional facts for this bread?

Hi Christina! I’m afraid I don’t. Check out “my fitness pal dot com” or another site for nutritional information.

Hello!

I followed your guidelines to a T. I had perfect float for my starter and proceeded with your recipe. After the 14 hours in the fridge I placed it in the heated 500 oven/turned it down to 450 then took the lid off and saw a sad almost flat loaf. After all that work what could have gone wrong? I haven’t cut it open yet. Maybe it still tastes ok but looks nothing like your bread.

Hi Linda! Bummer to hear this. With sourdough, there are any number of places things can go wrong.

Question: is your starter strong and active? Have you had success using it with other sourdough bread recipes? Does it double in volume within 4 to 6 hours after a feeding?

This Troubleshooting Post may help you identify your issues.

I’ve tried what certainly feels like every sourdough recipe known to Google and this is by far the best – I’m almost embarrassed by how outrageously complimentary people are, even those who do not usually eat bread.

Despite much experimenting with adding different flours and flavours, from whole wheat to rye to semolina to fresh chopped rosemary, to cumin and caraway to fat black and green olives, it always performs reliably and superbly. That extra day (or two) in the fridge seems to be a very special trick and really makes a difference to the lightness of the crumb.

Many thanks indeed, Alexandra. You deserve many more than 5 stars for this one!

Oh Barbara, so nice to read all of this. Thank you. All of your variations sound lovely, too. I am dying to make an olive loaf. Thanks so much for taking the time to write!

Ali, thanks so very much for your clear and concise directions. What a pleasure to find Alexandra’s Kitchen! For years I have made no knead style breads and have always wanted to try breads with a starter. I researched several of my bread books and bought a new one and ordered starter from King Arthur. I had some initial success but then started to have trouble with slack dough and flat loaves. It was not until I found your “sourdough demystified” tips about bulk fermentation and using the fridge for proofing that I understood my errors. I am finally happy with the outcome of my sourdough loaves and focaccia. I recently purchased your beautiful cookbook. The peasant bread recipe is lovely. Do you ever use a starter with this bread and if so what do you do differently? Thank you for all of your wonderful photos, videos and instructions!

So nice to hear all of this, Susan! And thank you so much for buying my book. Means the world 🙂 Yes, I do use a starter with the peasant bread sometimes. This focaccia bread recipe and this sandwich loaf recipe essentially are the peasant bread proportions but with a sourdough starter added to the mix and the water reduced slightly. You can use either of those recipes and after the bulk fermentation, split the dough in half, transfer to buttered Pyrex bowls, and let the dough rise at room temperature till it crowns the rim of the bowls.

I also have a hybrid yeast-sourdough discard recipe, which I share in this troubleshooting post.

Let me know if you have any other questions! Thanks so much for writing 🙂

I have attempted the recipe several times now with all-purpose flour and get a decent loaf every time. Your recipe is magnificent and easy to follow!

BUT of course when it comes time for shaping it’s always much too wet and I end up adding more flour, even when starting with –50g water. I went out and bought bread flour as you recommended, but I don’t notice much of a difference these last couple times when trying to shape. I tried to follow all other procedures exactly… I wonder if you have any thoughts?

Hi Lindsay! A few thoughts: you could try reducing the water by another 50 grams and see if that makes a difference. You could try shortening your bulk fermentation. How many hours on average would you say your bulk fermentation is?

It’s on the short side, usually close to the 4 hours. My kitchen is around 70 degrees in the daytime. Yes, less water to start definitely helps and the taste doesn’t suffer too much! Just wondering whether there was a way to maintain the hydration ration without having a puddle of dough. Thanks for the tips!

I had great results with this, although modified proportions and increased hydration modestly when doing my folds, b/c dough felt a bit tight. Used a mix of AP and KA white whole wheat (b/c that was what I had) and only a couple grams of salt.

My kitchen is cool, so did the bulk ferment overnight for the full 12 hrs and proofed for just 4 in the kitchen w/ good flavor and crumb. Bake times accurate, but w/ my oven I preheat at 500 and drop to 450 when I put in the loaf using my knock-off Dutch oven.

Newer to natural sourdough, but found the advice to avoid over fermenting key to correcting defects I’ve had in past loaves.

Great to hear all of this, Patrick! Thanks so much for writing and sharing your notes. So helpful for others.

After months of sourdough fails, THIS RECIPE worked perfectly! Your tips were incredibly helpful. I live in Houston, so I lowered the water amount. I also didn’t use the oven to proof: I had no idea how much the pilot light was throwing off my final “puff”. In the end, my loaf came out whole foods bakery perfect. It was doomed and had these lovely honeycomb-like air pockets within. Thank you, thank you!

Wonderful to hear this, Allison! I am constantly amazed by how the pilot light causes trouble for people … you wouldn’t think it could, but sourdough is just so sensitive. Thanks so much for writing!

I make this recipe regularly (it’s great!) and decided to spring for a dough bucket (the 4 qt Cabrio) and have a wonder (sorry if you addressed this already- so many comments to read I gave up looking after a while)…. is it important to cover the dough bucket with something porous like a tea towel or breathable bowl cover or can one use the lid of the bucket? Thanks Ali- from one of your fans!

Hi Sela! So nice to hear this, thank you 🙂 If you are storing the dough in the fridge, you can use the lid the bucket comes with. When you are doing folds/turns and letting the dough bulk ferment at room temperature, I would use a tea towel or something else that is breathable. Let me know if there is anything else. Enjoy the bucket! I find it so helpful for assessing the bulk fermentation.

Thanks to this tutorial, videos and recipe, I now bake sourdough at least once a week if not more. Thanksgiving week I made 6 loaves – for us, neighbors and family! Thank you again Ali for these recipes. I just ordered the large loaf pan so I can make sandwich/toasting loaves next!

The only issue I had was that initially I struggled with a very tough bottom crust and I couldn’t figure out why. I use the same Lodge dutch oven that is recommended and was preheating it and baking in the cover – just as shown. I tried not preheating the DO but that didn’t seem to help. I’ve finally found that for my Wolf oven I simply preheat the oven to 450 degrees, bake in the cold DO covered for 20 minutes, turn the oven down to 400 degrees, remove the cover and bake for another 20. My loaves now come out golden brown with a bottom crust that’s tender and “cuttable”. 🙂

Lindsay! So great to hear all of this. First: how nice of you to share bread on Thanksgiving … no better gift 🙂

Second: nice work experimenting until you found a method that worked for you. I truly feel this is what sourdough is all about — trial and error and finding a path that works for you. So glad your loaves are turning out with nice bottoms 🙂 🙂 🙂 Truly, there’s nothing worse than a super tough crust.

Happy happy holidays to you!

And to you and your beautiful family Ali!!

Can I double the recipe and bake it as a larger loaf and if so for how long?

Hi Courtney! A double loaf will be quite large … do you have a pan large enough to fit this size loaf? If so, go for it! I would do the same temperature, and I would bake it covered for the same amount of time (30 minutes); then bake it uncovered for longer — you’ll have to use your judgment. I would guess another 25-30 minutes.

Good luck with it!

Hey Ali!!

Thank you for your concise directions. They are so simple and make me feel successful!

I’m wondering if I can double this recipe to make a larger boule in a bigger Dutch oven. How would that effect bake time?

Hi Darcy! Yes, you absolutely can. I think bake time should be: covered for 30 minutes (so, the same); then uncovered for probably 25 minutes or so…just keep an eye on it and bake it till it’s browned to your liking.

I have lots of friends that make this type of bread but use yeast instead of a starter. I don’t have a starter and don’t know where to buy one can I use yeast?

Hi Lori! If you want to use yeast, I would try this recipe: Jim Lahey’s No-Knead Bread It will give you that crackling crust and it calls for a small amount of yeast and a long overnight rise. Good luck!

I followed the directions to a T. I used 50g of Oregon dark northern rye. It was a sticky mess to stretch and fold and generally work with but it baked beautifully – great crumb, nice rye and sourdough taste. Pat M.

Hi Pat! Great to hear it turned out well. The dough definitely is sticky. You can try reducing the water by 25 grams or so to see if that makes the experience more enjoyable without compromising the texture/flavor.

Hi. I’ve tried your brioche cinnamon roll recipe and it, by far, is better than the cinnamon roll recipes I’ve made in the past. Thank you.

Now I’m moving on to sourdough bread. Last week I made my first loaves and followed King Arthur Flour natural leavened sourdough recipe almost to a fault. The loaves came out great, and with more confidence than when I started, I began to check out other sourdough recipes. Because I was so impressed with your brioche cinn roll recipe, I checked our your website, and I’ve watched your videos and read through your sourdough “wheatish” bread recipe. If you have the time, could you please answer a few questions, as I imagine your are familiar with KAF’s recipe and process.

1) Why does your bread use such little starter (100g) compared to KAF recipe(227g) per loaf? I want to try your recipe, but I’m afraid my starter might not be “powerful” enough. 2) Their hydration is about 59%, and I still arrived with 2 lofty loaves, lots of holes and very light. Why is 70-75% the magic number? There are so many recipes with different ratios out there, I was wondering how you ended up with your specific recipe. Trial and error? Thank you for your time.

Hi Liz! Great to hear all of this. Could you send me a link to which KAF sourdough bread recipe you are using? I’d love to read through their process.

To answer your questions:

Why does your bread use such little starter (100g) compared to KAF recipe(227g) per loaf?

Honestly, I think it’s all relative 🙂 The first sourdough bread recipe I made called for 50g of starter for 500g of flour. It worked just fine, but I like using more starter, mostly because I like using my starter — I try to keep my starter on the lean side, but even so, when I feed it, I always have more than 100 g of starter, and I like to use most of it when I bake as opposed to storing it, after which time it may get discarded.

I want to try your recipe, but I’m afraid my starter might not be “powerful” enough.

I have a feeling your starter is just fine, but to be sure, next time you feed it, monitor how long it takes to double in volume. If it doubles in volume within 6 hours (or even a little bit more), it will be fine. If it doesn’t, consider feeding it twice a day for a couple of days.

Their hydration is about 59%, and I still arrived with 2 lofty loaves, lots of holes and very light. Why is 70-75% the magic number? There are so many recipes with different ratios out there, I was wondering how you ended up with your specific recipe. Trial and error?

That’s great re KAF recipe and your results. There is no magic number. I personally, like the taste of a very high-hydration loaf. This is likely because my mother’s peasant bread is the bread I grew up on, and that bread is 94% hydration. For me, 75% hydration is about as high as I can go with sourdough without the dough becoming unmanageable (though recently I’ve experimented with high hydration doughs and am having some success).

You may try this recipe and find the dough to be too wet and sticky and tricky, and if that is the case, you can always, next time around reduce the amount of water or go back to your tried and true KAF sourdough bread recipe… no reason to mess with a good thing 🙂 🙂 🙂

I like your recommendation to use a clear tub for the bulk rise. I’m a bit confused about how much it should rise. You mentioned 50% but also mentioned double or 100%. Can you advise? Thanks!

Hi Adam! When I was first making sourdough, I almost always let the dough double. Now, I stop the bulk fermentation when the dough has increased by 50%, and that is what I recommend people do. I find I get a loftier, lighter loaf when I stop the bulk at 50%; then do a cold proof for at least 24 hours. I need to find the spot in the text where I recommend doubling … I thought I had edited those all out.

I just made your ricotta recipe and was wondering if I could use the whey in this recipe for the water? I wasn’t sure how that would effect the starter, if at all. Thanks in advance!

Hi Kristen! It might work out just fine, but I’ve never tried so I can’t say for sure … I’ve used it in yeasted breads, but yeasted breads are so much more forgiving. Sourdough can be a little finicky. My gut is that yes, you can use it or use some of it for the liquid, but again, I haven’t tried, so I don’t know how to advise. Keep in mind, too, that the whey is a little bit salty.

I gave it a shot and found that my dough rose much quicker than it usually does though maybe my kitchen was a little warmer at the time. It definitely worked but I found the finished product to be a little too chewy/gummy. It won’t go to waste though. I figure it will still make excellent toasted bread crumbs. Next time I’ll make it with water and I know it will be fabulous. You’re blog and cookbook are my go tos for bread recipes. I will try the whey in a yeasted bread next time I make the ricotta. Which is fabulous, by the way. I’ll never buy store bought again unless I’m in a pinch! Thanks for the quick reply!

OK, great to hear all of this, Kristen! It’s always so interesting to me how little changes like this in a recipe cause it to rise and bake so differently. Glad you’ll make good use out of it. And thank you for the kind words … means a lot 🙂 🙂 🙂 And yay re homemade ricotta. I love that recipe so much!

Hi when I bake for 30 min it’s not done, looks like half cooked dough. I use the ikea Dutch oven and preheated it. I do not know if I should bake longer or use higher temp for baking! Any advice is appreciated.

How long are you preheating the Dutch oven for?

Hi I place the Dutch oven in the oven while it preheats perhaps approximately 10 min. Should I be preheating the DO for longer? Or should I bake on 450F for longer, so far my 2 attempts were unsuccessful during baking phase. All other steps were fine.

Hi! I preheat my Dutch oven for the entire time the oven is warming up and often an additional 20-30 minutes. Some recipes suggest preheating your DO for at least 45-60 minutes, so increasing that preheating time would be my first suggestion. Try that; then you can adjust with other moves: increasing your oven temperature, increasing total baking time, etc.

Thank you very much I tried your suggestion and and it worked. But in the end the crust was too hard and the crumb was very gummy. I will have to try again, but at least now I know that preheating Dutch oven works!

Hi Ali,

I just finished my bake today. The flavor was outstanding but I need some help with crumb issues.

The only changes to the bread formula was to reduce the water ~ 5%. I find that I typically need to do that with my sourdough bakes due to the high humidity where I live (Seattle, WA area). I kept the dough in my proofer during bulk ferment and the dough temp ranged from 69-71 degrees F. Total time to reach 50% (measured in square Cambro container) was ~ 7 hours. The dough was pre-shaped and bench rested for 30′, After final shape the dough was cold retarded for ~ 23 hours. I preheated the oven as suggested and followed the baking times and temps from the recipe while using clay bakers for the loaves, The final DT was 208-209 degrees F.

The problem I had after cutting the cooled loaf (3 hours) was a somewhat gummy, sticky crumb and some large irregular holes. This surprised me because the dough shaped and handled nicely before the cold retard. The other interesting outcome was the exaggerated and uneven opening of the scoring.

Hope you can help with suggestions because I loved working with the dough.

Hi Bruce! Great to hear all of this. It sounds as though you are doing everything right, so it’s hard to pinpoint what could have led to the gumminess. My first thought is to potentially reduce the water even more. Maybe try using 275 g water. Second: what type of flour are you using?

Finally: when you do the stretches and folds, do you notice the dough getting stronger with each set?

And one other thought is about the starter. Are you confident in its strength?

Hi Ali,

Thanks for reviewing and giving me some great input.

The flour I was using was a blend of 70% bread flour (Cairnspring Glacier Peak, Protein 13-14%, T 70) and 30% all-purpose (Central Milling, Protein 11.5%). I subbed in some AP to make it softer for my wife.

The dough did strengthen with the S&F’s and was really nice to work with when shaping. It also held its shape well during the bench rest.

I checked my starter today and measured a 2.5X growth in 6 hours with many fermentation bubbles.

The only other piece of information is that my slicer blade had sticky residue when I sliced the loaf.

Bruce

Ok, thanks, Bruce! Again, it sounds as though everything went well with the bulk fermentation, so I don’t think it over-fermented. So, I think it possibly has to do with there being too much water (though if the dough was easy to handle, then I’m not convinced this is the issue).

The only other thing I can think of is the baking process itself. Do you preheat a clay baker? I’m not totally familiar with them. And have you been happy with other loaves you’ve baked in your clay baker in terms of doneness? Part of me wonders if the loaf needed to cook longer? The wet, sticky crumb is leading me to think either the loaf needs to cook longer or the water needs to be reduced.

Good Morning Ali,

Thanks for the quick response and great feedback. The clay baker has typically worked well for me. I think I will pursue a longer bake time on my next try. I also might add a small amount of stone ground whole wheat to help with hydration level.

I sure am enjoying the recipes on your website. I am making the baked steel cut oats again this morning 😊

Sounds great, Bruce! And thank you for your kind words 🙂 Love those oats!

Great recipe! The bread was delicious and this will certainly be my go-to recipe! For a Pullman loaf pan, what temp, time or any other changes to this recipe do you recommend?

James

Great to hear James!

For the pullman loaf, I proofed this in the fridge for about 12 hours in its pan — I lightly slick the dough with oil to prevent it from drying out, and I stick the pan in one of those plastic produce bags and tie a knot; after the 12 hours: let it rise at room temperature for roughly 5-6 hours before baking at 400ºF for about 40 minutes.

I’ve been making this almost weekly since I received a scale for Xmas and it’s SO good!!

Great to hear this, Amy!