Why is my sourdough so sticky? 4 Common Sourdough Mistakes + Answers to FAQ’s

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read my disclosure policy.

We all face failure, at some point, when making sourdough bread.

Common troubles include:

- an impossibly sticky dough

- a just-baked loaf looking more like a pancake than a lofty boule

- a crust so tough it might rip your teeth out

- a dense, gummy crumb

Sourdough is a journey. Failures are a rite of passage.

If you can embrace the failures, learn from your mistakes, and make changes based on your results, you will find success.

Earlier this year, when the interest in sourdough surged among the many people housebound, I received more questions about sourdough bread baking than anything else. Often: Why is my dough so wet and sticky? But also: How can I get better oven spring? And frequently: How can I make sourdough without being up till midnight?

In responding to the various inquiries, I noticed some trends and can trace most sourdough troubles to just a handful of issues.

This post is organized as follows:

If I haven’t addressed one of your questions, please leave a comment below. Or if you still need clarification on something, leave a comment. I intend to update this post regularly.

Finally: I collected much of the information below while engaging with people who signed up for my free Sourdough: Demystified! email course. If you’d like to learn the basics of sourdough bread baking, sign up here: Sourdough: Demystified!

Where Sourdough Goes Wrong: The 4 Common Mistakes

I am assuming everyone reading this is baking with a scale. If you are not measuring your flour, salt, water, and sourdough starter with a digital scale, that is the first change you need to make.

The 4 Common Mistakes:

- Using a weak starter or not using starter at its peak.

- Using too much water relative to the flour.

- Over fermentation: letting the bulk fermentation (first rise) go too long.

- Using too much whole wheat flour, rye flour, or freshly milled flour.

1. Using a weak starter or not using starter at its peak.

When you set out to make a loaf of sourdough bread, you first need to make sure your starter is ready — it has to be strong enough to transform a mass of dough into a lofty boule.

How do you know if your starter is ready? When it …

- … doubles in volume within 4 to 6 hours (roughly) of feeding it.

- … floats when you drop a spoonful of it in water.

Both of these are good signs your starter is ready, but in my experience, #1 is a more reliable test than #2. If your starter is not doubling in volume within 4 to 6 hours of a feeding you should spend a few days strengthening it. This is what I always recommend:

- Be aggressive with how much of it you are discarding: throw away most of it, leaving behind just 2 tablespoons or so. Feed it with equal parts by weight flour and water. Start with 40 g of each or so.

- Use water that you’ve left out overnight to ensure any chlorine has evaporated. (This isn’t always necessary, but it might make a difference.)

- Buy spring water. In some places, letting water sit out overnight will not be effective, and your tap water may kill your starter.

- Feed your starter with organic flour or a small amount of rye flour or stone-milled flour (fresh or locally milled if possible). My store sells 2-lb. bags of King Arthur Flour organic all-purpose flour for $3.49 — I use it exclusively for feeding my starter.

- Once you feed your starter, cover the vessel with a breathable lid, and leave it alone at room temperature. After 6 hours (more or less), repeat the process: discard most of it and feed it with 40 g each flour and water.

Once you have a strong starter on hand — one that is doubling in volume within 4 to 6 hours — you can bake with it (using it at its peak doubling point) or stash it in the fridge. When you feed your starter, place a rubber band around the vessel to mark the starter’s height, which helps gauge when it has doubled.

My preferred storage vessel is a deli quart container. When I store my starter in the fridge, I use the lid that comes with the quart container. When I feed my starter and let it sit at room temperature, I use a breathable lid.

Moving forward, you should remove your starter from the fridge a day before baking, discarding most of it and feeding it at least once but ideally twice (if you have time) before using it.

Finally: There is no shame in purchasing a starter. I am a huge proponent of purchasing a starter, which is guaranteed to be vigorous nearly from the get go. Building a starter from scratch is a great exercise, but the reality is that your starter, in the end, might not be as strong as you need it to be to bake a lofty loaf of bread.

Two sources for sourdough starter: Breadtopia and King Arthur Flour.

2. Using too much water relative to the flour.

All flours absorb water differently. Bread flour, all-purpose flour, whole wheat flour vary from brand to brand in their protein content and overall makeup. Environment (humidity in particular) plays a role in water absorption, too.

If, for example, I mix a dough made with 100 g starter, 300 g water, and 400 g bread flour in Upstate New York and you do the same wherever you are, even if we’re using the same brand of flour, the texture of the dough may look and feel very different. If you live in a humid environment, your dough may look soupier. If you live in a dry environment, your dough may look stiffer.

The solution? Experiment! Use a recipe as a guide. If you are using a recipe with a hydration of 75% or higher (300 g water to 400 g flour, for example) and you live in a humid environment, consider holding back some (50 g or so) of the water. You can always add some of it back in slowly if the dough feels too stiff. Always measure by weight, and take notes.

A general rule of thumb to consider is that the higher the protein content of a flour, the more water will be absorbed. Same for whole grain flours — whole grain flours absorb more water, so when you use whole grain flours or bread flours (which are generally high in protein), the dough may require a little more water. All-purpose flours may need less water.

Once people fiddle with the water level of a recipe — usually by cutting it back by 50 g or so — their troubles are mostly solved.

3. Over fermentation: letting the bulk fermentation go too long.

The bulk fermentation is the dough’s first rise: it’s the time period that begins when the dough is mixed and ends when it is shaped.

Unlike yeast-leavened doughs, which often call for letting the dough rise till it doubles (or more) in volume, with sourdoughs, you don’t want it to rise so high.

Opinions vary on what percentage increase is optimal. Some bakers suggest a 30-50% increase. Others suggest a 50-75% increase. Others suggest more.

As with determining the ideal hydration of your dough given your environment (as discussed above), determining the ideal increase in volume may take some trial and error.

The more sourdough I bake, the more I find it beneficial to stop the bulk fermentation when the dough has increased by roughly 50% in volume. Keep in mind, with the exception of focaccia, I almost always follow the bulk fermentation with a long, cold, refrigerated proof.

Why is this important? Here’s a general rule of thumb: if you’re going to do a short (4 to 6 hours), room temperature proof before baking, you can allow the dough during the bulk fermentation to increase by more. If you’re going to do a long, cold proof, stop the bulk fermentation when the dough has increased by 50% or less in volume.

The length of time it takes for your dough to increase by 50% in volume depends on a number of variables, including the strength of your starter, how much starter you use, the hydration of your dough, the type of flour you are using, the humidity, and the temperature of your kitchen.

When the dough has visible bubbles throughout and has roughly increased by 50% in volume, it’s ready to be shaped.

When the bulk fermentation goes too long — often when the dough more than doubles or triples in volume — the dough can over ferment. You know the dough has over fermented if, when you turn it out to shape it, it is very slack — if it’s like a wet puddle — and very sticky and lacking any strength and elasticity. It might smell a bit like alcohol as well.

At this point, the dough unfortunately is unsalvageable.

To prevent dough from over-fermenting:

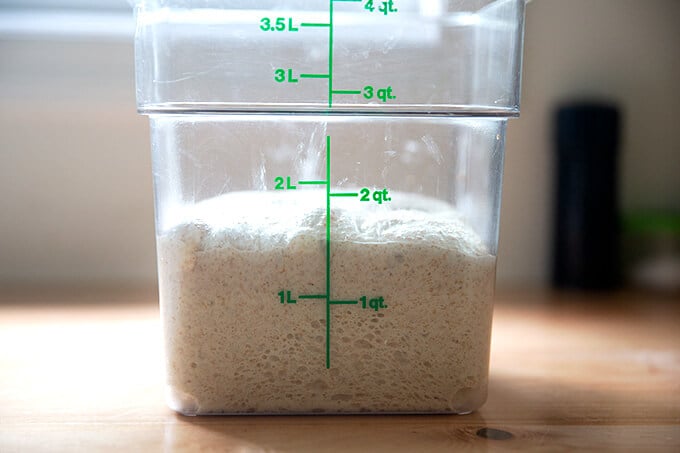

- Let the dough rise in a clear, straight-sided vessel (such as this one). Unlike a bowl, a clear straight-sided vessel allows you to see the bubble activity throughout the dough, but also lets you accurately see how much the dough has grown in volume. In the photo above, the dough has increased in volume by 50%. A straight-sided vessel allows you to accurately gauge the increase in volume.

- Use the refrigerator as needed. At any point during the bulk fermentation you can stick your vat of dough in the fridge to slow the fermentation. If, say, your dough is rising but you are tired and need to go bed, stick the vessel of dough in the fridge, and pick up where you left off in the morning.

A warning: I do not recommend letting your dough do the bulk fermentation in your oven with the light on. Many people try this, especially in the winter, and while some have success, others do not — the environment is just too warm and, as a result, the risk of over fermentation is too high.

4. Using too much whole wheat flour or rye flour or freshly milled flours.

People love incorporating rye and whole wheat flours into their breads mostly for health reasons but also for flavor.

When anyone asks me how to incorporate more whole wheat flour into a loaf of bread, the first thing I ask is: “What type of whole wheat flour are you using?”

And the reason I ask this is that commercial whole wheat flours aren’t necessarily healthier than commercial all-purpose flours or bread flours.

I go into more depth on this subject in this post, Favorite, Easy Whole Wheat-ish Sourdough Bread, so I’ll summarize: if you want to truly introduce healthy flours into your breads, you are better off using freshly milled, stone-milled flours — the milling process of these flours keeps the bran, the germ, and the endosperm together, which in turn preserves the nutrients. (Read more about this here.)

You can order these flours online or search for them at a farmer’s market or local co-op. These types of flours add tremendous flavor and aroma to breads. That said, these flours can be difficult to work with for two reasons:

- Because whole grain flours absorb more liquid (due to the presence of fiber particles), they require more liquid, which makes the dough wetter. Wet doughs are tricky to work with, and if you are new to sourdough, shaping a very wet dough or trying to create tension can be frustrating and discouraging.

- Whole grain flours tend to make for a denser crumb. Due to the presence of the bran, which often is likened to a razor blade that cuts the gluten bonds and impedes gluten development, breads made with a high proportion of whole grain flour won’t have a light, airy crumb. There is nothing wrong with this, but you should manage your expectations as soon as you introduce whole grain flours into your doughs.

I always encourage people to start by using 100% bread flour or all-purpose flour. Once you get the hang of the sourdough process and the various phases, then start introducing whole grain flours into the mix. Start by swapping out 12-15% of the white flour for whole grain flours; then increase to 25% (and so on) if you are happy with the results.

I love adding cornmeal, both for flavor and texture, into my bread doughs:

How to Keep a Lean Starter

A common question I get is: What do you do with all of the discard? I have one suggestion below, but the truth is that I don’t bake with a lot of discard because I don’t have a lot of discard on hand.

I keep a very lean starter.

This is my starter maintenance routine: I have one vessel (a deli quart container) for my starter, and I only keep about 100 g of it on hand at one time. I store it in the fridge, covering it with the lid that comes with the quart container.

When I am ready to feed it, I remove it from the fridge, discard most of it, leaving behind just 2 tablespoons or so; then I feed it with 60 g each flour and water, cover it with a breathable lid, and let it sit at room temperature for 4 to 6 hours or until it doubles.

When it doubles, it’s ready to be used in a recipe, and I scoop out the amount required. After I use it, I replenish it with a small amount of flour and water (40 g each water and flour); then I stash it in the fridge.

When I am ready to bake again, I repeat the process: discard most of it, feed it, let it double, use it.

FAQ’s

When do I use my starter?

Use your starter when it doubles in volume, usually 4 to 6 hours after a feeding.

If your starter is not doubling in 4 to 6 hours, you should spend some time strengthening it. See #1 above: Using a weak starter or not using a starter at its peak.

How do I keep my starter alive?

Many people don’t get into sourdough bread baking because of the perceived demands of a sourdough starter. They worry: It’s like having a pet!

The truth is that starters are not as needy as people think. I have left my starter for 3 to 4 weeks at a time in the fridge without feeding it, and it always revives beautifully.

When I neglect it for this many weeks, I’ll spend a day or two getting it back to strength. See my starter maintenance routine above in the How to Keep A Lean Starter section.

What’s a good baking schedule to follow?

People often ask: What is a good schedule to follow? How do I avoid baking bread at midnight?

There are various schedules you can follow, but my biggest tip in regard to making sourdough work with your schedule is to use your refrigerator.

For whatever reason, I often find myself mixing bread doughs in the evening. Because of this, I find myself wanting to go to be in the middle of the bulk fermentation (first rise). In the winter, I can get away with letting the dough rise over night on the counter, but in the summer, it’s a gamble — when the bulk fermentation goes for too many hours, the risk of over fermentation is high.

So this is what I do: after I do at least two to four sets of stretches and folds (see this post if you are unfamiliar with stretches and folds), I cover the vessel, and stash it in the fridge. In the morning, I remove the vessel from the fridge, set it on the counter, and pick up where I left off, letting the bulk fermentation continue until the dough increase in volume by 50% (roughly).

Then I’ll turn the dough out, shape it, and refrigerate it for another 12 to 48 hours before baking. So, the next tip: plan ahead. If I first mix the dough Wednesday evening, I likely won’t bake it till Friday.

Here’s a sample schedule:

Wednesday: Get my starter ready. If I am baking frequently, I can remove my starter from the fridge, feed it once, let it rise till it doubles, then use it. Sometimes I’ll feed it twice. Often, as noted above, I mix my dough in the evening, let it rise for a couple of hours, then stick it in the fridge to prevent it from over fermenting over night.

Thursday morning: Remove dough from fridge, let it rise at room temperature until the bulk fermentation is complete (when the dough has increased by 50% in volume). Shape it, transfer it to a flour sack-lined bowl, and refrigerate for 12 to 48 hours. (Note: If Thursday morning you have to go to work, rather than take the dough out of the fridge in the morning, take it out when you get home from work. Let it rise at room temperature till it increases in volume by 50%; then shape it and return it to the fridge.)

Friday: Bake it at my convenience.

Here are two easy sourdough boule recipes to test out this schedule:

How do I get better oven spring? In other words, how can I create a loftier boule?

Good oven spring is based on a number of factors. As noted above, if your starter is weak, if your dough is overly hydrated, if the dough over ferments, if you use too much whole grain flour, you may end up with a squat, dense loaf.

If, however, you feel confident in all of the above — strong starter, proper hydration, optimal bulk fermentation, good mix of flour — then oven spring can be affected by:

- Creating good tension during shaping.

- Cold proofing.

- Proper scoring.

- Using a good baking vessel.

Creating tension: This takes practice. When I shape, I like to use an un-floured work surface, and I like to use a bench scraper. Here is a video of me shaping a high-hydration dough, but I highly recommend poking around YouTube for other videos from more skilled shapers.

Cold proofing: Because a cold environment slows down fermentation, a shaped loaf of sourdough needs to proof for a longer period of time than a loaf proofing at room temperature. And because cold gasses contract in volume, a loaf of refrigerated sourdough needs more time — needs to accumulate more gas — to become fully proofed. In his book Open Crumb Mastery, Trevor Wilson says: “More gas equals more oven spring.”

Proper scoring: Scoring a loaf helps it fully expand in the oven — an unscored loaf might burst in unexpected (weak) spots of the dough and will not rise to its full potential. (See image above.)

Like shaping, this takes practice. You want to score the dough swiftly and confidently. A sharp blade helps. Start with a simple slash down the middle for oblong loaves. Start with a simple “X” for round loaves.

I find scoring a cold dough much easier than scoring a room temperature dough, which is another reason why I’m a fan of the cold, refrigerator proof. Regardless if the dough is cold, however, you want to make a 1/2-inch deep (roughly) score into the dough.

A good baking vessel: The reason many sourdough bread recipes call for baking in a preheated Dutch oven is that the sealed environment creates a hot steamy place for the bread to rise. In Tartine Bread, Chad Robertson writes:

“Baking your bread in a cast-iron combo cooker gives you the same results you’d get with a professional deck oven by creating a completely sealed, radiant-heat environment. The loaf itself generates the perfect amount of steam until you remove the cooker lid to allow the formation of the crust to finish the bake. The cooker’s sealed steam-saturated chamber gives considerably better results in oven spring and score development than baking a loaf on a baking stone placed in a home oven.”

I can recommend two great baking vessels.

- This is the 5-Qt Lodge Double Dutch oven I used exclusively for sourdough bread for years. As far as Dutch ovens go, this one is on the more reasonably priced side ($50). Yes, it is an investment, but if you are after that crackling crusted lofty boule, it will be worth every penny.

- This was a recent splurge: The Challenger Bread Pan. If you are more interested in baking batards or other oblong-shaped loaves (in addition to round boules), this is a great pan. The handles on the lid make it an especially nice user experience. Yes, it is expensive ($295). If you are committed to sourdough and bread baking in general, I don’t think you will be disappointed in this investment.

This is the 5-Qt Lodge Double Dutch oven:

What if I don’t have a Dutch oven?

If you don’t have a Dutch oven, you can do several things. Know, however, these alternative methods will not give you the same results as a Dutch oven. I can’t encourage you enough to invest in one of the two pots mentioned above.

Options:

- Preheat any oven safe pot with a lid.

- Preheat oven safe pot with a sheet pan placed over top or vice versa: a sheet pan with a pot inverted over top.

- Preheat a Baking Steel or baking stone with a pot inverted over top.

- With any of these methods you may want to also preheat another smaller vessel (such as a cast iron skillet), into which you could throw some ice once the bread has been placed in its baking vessel. As the ice melts, it will release steam, which as discussed above is good for oven spring.

What to do with the discard?

As discussed above, I don’t do much baking with discard because I keep a very lean starter. And while I have been been very pleased with using discard in these sourdough flour tortillas, in this Irish soda bread recipe, and in my favorite pancake recipe, my favorite thing to do with discard is to: make more bread!

I use my mother’s peasant bread recipe but you can use any bread recipe you like, so long as you have the weight measurements. So, if I want to use 100 g of discard (assuming this is made with equal parts by weight flour and water) in a bread recipe, I’ll simply subtract half of the starter weight (50 g) from the flour and half from the water.

For my mother’s peasant bread recipe, these are the proportions:

- 462 g flour (512 g minus 50 g)

- 404 g water (454 g minus 50 g)

- 10 g salt (same amount)

- 8 g instant yeast (same amount)

- 8 g sugar (same amount)

You can use any amount of starter you have on hand — just adapt the recipe accordingly. As I said above, do this with any yeast-leavened bread recipe you like.

I love making bread with discard, because while my sourdough slowly materializes over the course of a few days, I can enjoy delicious, freshly baked bread in three hours.

My bread is burnt on the bottom. How can I prevent this?

If you are using a preheated Dutch oven, consider lowering the temperature.

Before you make changes to the temperature, however, next time you bake, check the dough after 30 minutes. If the dough is browning too much on the bottom, you know that it’s happening during these first 30 minutes, in which case, you should lower the temperature from the start. Decrease it by 25ºF.

If the dough is not browning, then you know the burning is happening during the last 15-20 minutes of baking, in which case you could remove the loaf from the pot after 30 minutes and bake it on a sheet pan.

Another option: place your Dutch oven on two sheet pans. I do this with challah to prevent the bottom from burning. The extra layer of sheet pans will prevent the bottom of your sourdough from burning, too.

Another option: place your Dutch oven on a broiling pan.

Finally: Use rice flour for dusting — it makes all the difference. It does not burn the way wheat flour does. It also doesn’t coat the loaves with an unpleasant raw flour taste. One bag will last you a long time.

How do I know if my dough has proofed sufficiently?

Just to clarify: the bulk fermentation in essence is the first rise. I discuss assessing the bulk fermentation above. Proofing in essence is the second rise — the phase after the dough is shaped.

Confession: I never do any test to see if my dough has sufficiently proofed. This is because I know if the dough has properly fermented during the bulk fermentation (i.e. not over fermented), and if I know the dough has spent enough time in the fridge (at least 12 hours but up to 48 hours); then I know it has sufficiently proofed.

If, however, you want to do a test, a common one is the “finger poke” test.

In his book Open Crumb Mastery, Trevor Wilson writes:

“As its name implies, the finger poke test is just that — a finger poke. As commonly prescribed, the baker should poke a finger into the proofing loaf about a half-inch deep or so. If the dough springs back completely and quickly, then that means the dough is not ready to bake. It’s still underproofed. If the dough barely springs back — or doesn’t spring back at all — then that means the dough is past its peak. It has overproofed. If, however, the dough slowly springs back completely or almost completely, then that means it’s just right.”

To be clear, Trevor finds this test to be problematic for a number of reasons, and if you want a more in depth explanation, download his book.

In short, in my opinion, if you take care in making sure your bulk fermentation is the proper length, and if you do a cold, refrigerator proof, you don’t have to worry if your dough has over or under proofed.

How to convert the Fahrenheit temperatures to Celsius, gas, and fan forced?

Use this handy table.

What is the difference between a levain and a starter?

There are a number of definitions out there for levain or leaven, but think of a levain simply as your sourdough starter’s offspring.

The Tartine Bread method of making naturally leavened bread uses this method. In short, it calls for using just a tablespoon of starter, which you mix with 200 g each flour and water and set aside to rise overnight. The following morning, you use this leaven in your dough.

How do I incorporate olives or other ingredients into my loaves?

Incorporate ingredients such as olives, nuts, sun-dried tomatoes, etc. in the early part of the bulk fermentation after you’ve done at least one set of stretches and folds. Before the second set, sprinkle the ingredients over top of the dough. As you do the stretches and folds, the ingredients will incorporate into the dough.

How do I get a more open crumb?

Achieving an open crumb is something I have not yet mastered.

As with many of the issues discussed above, it’s something, I’m hoping, that comes with practice — as I get better assessing the bulk fermentation, as I get better shaping and creating tension, as I get better using a delicate but confident touch while scoring, I am hoping I will see more of that beautiful, honeycomb open crumb in the boules I bake.

That said, there is only so much I am willing to do for a loaf of bread. This may come as a surprise to those of you who know how much I love bread, but it’s the truth. If you’ve made any of the sourdough bread recipes on this blog, you know I like to keep thing relatively simple, and I am unwilling to to do an autolyse, which always feels like too much work. (Autolyse, if you are unfamiliar, is the process of mixing the flour and water together and letting it sit for a period of time before adding the salt and the starter, a technique many sourdough bread bakers believe is beneficial for a number of reasons including dough extensibility/gluten development, crust color, and flavor.)

If you are after that open crumb, I highly recommend you download Trevor Wilson’s Open Crumb Mastery. I am currently making my way through it, and I am learning a lot, though I find it to be a bit overwhelming. With that in mind, it is not a book for beginners. It is intended for the intermediate sourdough bread baker.

For me, I think, it’s going to be a bit like Tartine Bread: a book I find myself returning to year after year, devouring it for stretches of time, then tucking it away for months till I feel moved again.

Open Crumb Mastery is packed with information, and if achieving an open crumb is a goal of yours, it’s definitely worth adding to your library. I have never read a sourdough bread baking book packed with so much information.

How do I make my loaves taste more sour?

There are a number of ways to make your loaves taste more sour, but my biggest tip is to do a long, cold, refrigerated proof. The longer time the shaped loaf spends proofing in the fridge, the more sour the flavor. Try for at least 24 hours but for as long as 48 hours.

Another tip: use less starter. It’s counterintuitive, but using less starter usually means your bulk fermentation will be longer, which means your starter will go through its food source at a slower rate and therefore produce more acetic acid along the way.

In my experience, I see little difference in both the length of the bulk fermentation and the resulting sourness in a loaf whether I use 50 g or 100 g of starter in a recipe. But if you are after more sour flavor, using less starter may be something to try.

How do I make my loaves taste less sour?

1. Room temperature proof. After the bulk fermentation and after you shape the dough and get it in its proofing bowl or basket, you can simply let the dough proof at room temperature for 4 to 5 hours or until it has proofed sufficiently and is ready to be baked. (See the reference to the (imperfect) poke test in the “How do I know if my dough has proofed sufficiently” section above).

2. Shorter colder proof. I prefer to do at least a 24 hour refrigerator proof because I find it make a big difference in my crumb structure. That said, the longer the dough spends in the fridge, the more tangy/sour the flavor gets. You can get away with a much shorter proof — 12 hours or so — keeping in mind your crumb might not be as light/open.

3. Use the levain method: At night before you go to bed, stir 20 g of sourdough starter (fed and at its peak) into 50 g water and 50 g flour. Let it sit overnight. In the morning, stir this levain into 300 g water, 10 g salt, and 400 g flour. Then proceed with the recipe through the shaping step. At this point, you can either do a room temperature proof or a shorter refrigerator proof. The levain method is what is employed in Tartine Bread, and it produces a less sour flavor.

4. Using starter at its peak. Be sure to use your sourdough starter at its peak or just before it reaches its peak after a feeding. Sometimes I don’t catch the starter at its doubling point, and I use it when it is a little “riper”, which makes for a more sour flavor. I prefer using it when it is not so ripe to ensure the flavor is not super sour.

5. Use more starter. As noted above in the “How do I make my loaves taste more sour?” section, using more starter will actually make the loaf taste less sour.

That said, this is true up to a point: if you make a loaf with 400-500 g flour and use 200 g sourdough starter, it is going to taste sour due to the high percentage of sourdough starter in the mix, which will lend a lot of sour flavor. To prevent a loaf of bread from tasting too sour, I wouldn’t use much more than 100 grams of starter for a 400- to 500-gram loaf of bread.

My crust is so tough. What can I do to prevent this?

A few thoughts. First, a sharp bread knife makes all the difference. Here are two I like:

- This one is attractive and reasonably priced.

- This one is a little more expensive, but also nicely designed and sharp.

Second, you try a different recipe, such as sourdough focaccia or sourdough sandwich bread.

If you are after a crusty boule, however, but you just want it a little less crusty, there are a few things you can do:

- Use rice flour as opposed to bread flour for dusting.

- Be sure you are using a good Dutch oven, which will create a good steamy environment during the first 25-30 minutes of baking. These are two I like: 5-Qt Lodge Double Dutch oven and The Challenger Bread Pan.

- Spray your dough with water before covering the Dutch oven.

- Lower the baking temperature. Continue to preheat your Dutch oven at a hot setting (500ºF or above) but lower the oven temperature to 425ºF when you place your dough in it. Bake it for 30 minutes covered. Uncover the pan and transfer the loaf to a sheet pan. Bake for 15 minutes more or so. If you have an instant read thermometer, it should register 207ºF or above to ensure the bread is cooked.

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read my disclosure policy.

164 Comments on “Why is my sourdough so sticky? 4 Common Sourdough Mistakes + Answers to FAQ’s”

Hi Ali,

I have been reading so many things about sourdough on the internet. One of them said that it is not necessary to let your loaf warm up when taking from the frig to bake, but could put it in the oven right away. What is your opinion on this? Thanks in advance.

Mary

Hi Mary! There is no need to let your dough warm to room temperature. I take my cold dough, score it, and transfer it immediately to my hot Dutch oven.

I found a recipe online, using the autolyse method. I knew after I poured the water in, it would be too much for my conditions. I should have held back. I followed through with all the stretching and folding, then put it in the fridge for about 42 hours. It was still really wet, sticky. I know adding a lot of flour is the wrong thing to do, so I tried to form it, and it didn’t want to. I usually do the no knead sourdough recipe from King Arthur, and they say you can use a Pullman pan. We prefer that, makes for a better sandwich bread. I tossed the gloppy mess in the pan and left to warm for a couple hours. I had no faith it would do anything, so I made sure I had fed my starter well…lol Imagine my surprise when this gloppy mess rose beautifully in the oven! It has a beautiful sourdough flavor, open crumb, I scored the top and it made a beautiful ear….lol

So nice to hear this, Terry! Glad you pushed on!

I just got a Dutch oven and have been using it like any old pot.

When using it as an actual Dutch oven, does it cook stuff on the stove top with the lid closed or is it put in the actual real oven? I never knew how this worked.

Hi Ken! You can use it both stovetop and in the oven. For the purposes of bread, it’s usually baked in the oven as opposed to stovetop.

Hi there! Thank you for your step by step guides. This may be a really stupid question, but I can’t seem to find the answer: If you feed your starter twice in one day before baking with it, do you discard twice (once before each feeding), or do you just discard before the first feeding?

Thank you!

Hi Jenni! I would discard before the first feeding only. Just so you know, however, there is no right way to do it, but the idea behind discarding a lot of your starter before feeding it (especially if it’s been stashed in the fridge or even left at room temperature for a long period without a feeding) is to remove a lot of acid — sometimes this is called the “acid load”. Too much acid is a bad thing. But after you feed it once, it’s unlikely that your starter will have accumulated a lot of acid before you feed it again. So, unless you’re worried about amassing too much starter, you don’t need to discard before the second feeding. Hope that helps!

Thank you so very much!!

Can I add millet to my sourdough bread. If possible, how do incorporate?

Yes! I would add it right in with the flour.

I have baked my own traditional bread for over 40 yrs but am new to sourdough. I am loving it and your advice. My question is, do you have this article in a printable format?

thanks so much,

Rachel

Hi Rachel,

Unfortunately, I don’t because it’s not a recipe. I’m sorry!

Hi Ali – great article, glad I found your site.

One question, sorry I didn’t check all 84 comments first, :), at the start of this article you list “a dense, gummy crumb” as a common problem; however, I don’t see mention of this and how to fix or address in your article? Maybe I just missed it? Thank you again. Best regards, Steve

Hi Steve, No, you’re right, I actually don’t specifically answer it, because I sort of address it throughout the post, but I should add a section … I will.

A dense gummy crumb can be a factor of a number of things:

1. Too much water relative to the flour. I think so much of sourdough is just getting the water level right given your environment and the flour you are using. It can take some trial and error.

2. Underfermented. Either the bulk fermentation didn’t go long enough or the proof didn’t go long enough. I love using straight-sided vessels to ensure the dough is rising 50-75% in volume before shaping it, and I now always do a cold 24 hour proof.

3. Overfermented. The bulk fermentation went to long and the gluten in the dough begins to degrade. This is another reason I love the straight-sided vessel.

Let me know if this helps!

This post is fantastic thank you so much! I’ve definitely been over fermenting my dough and feel so duh for not realizing it before… anyway as you say, this is a journey! I am having a small issue with my final product and cant seem to find an answer in the things I’ve read. My baked bread is getting a beautiful oven spring and is not dense but it is very moist, almost like its underbaked and I am not getting the approx 90 degrees C inside temp (granted I am measuring with a meat thermometer which could be why!? Although I do also feel like temp is temp?) This seems to happen regardless of how long I bake it for. The crust is developing beautifully but if I leave it longer and longer in the oven it just burns, obviously, but the inside stays tacky… and when I press it it kinda just turns back to dough… I tried to cook at a lower temp like what you describe at the bottom of your post, (C for me – 260 preheat and then 220 bake) covered for 30 mins then uncovered, I actually ended up baking it for over an hour in total… about 70/80 mins… I’m wondering if I’m still over fermenting? Or maybe under proving? Thanks so much!! Alila

Hi Alila!

A few thoughts: Are you using a scale to measure? If so, you could try cutting back the water by 50 grams or so.

It does sound as though you might still be over-fermenting however. The fact that when you press the crumb that it turns back to dough makes me thing that the dough has over fermented.

Are you confident in the strength of your starter?

Hey! Wow thanks for such a speedy reply. Yes I am using a scale and defs confident in the strength of the starter, as I said I am getting a great oven spring and the dough is not dense. I am using a recipe that is 75% hydration with 700grams of white bread flour and 300 grams brown bread flour, so it’s got 750 grams water. I do follow that exactly. But I think what I will do is test out doing an even shorter ferment for my next loaf and then the one after I’ll test out doing 700 grams water instead of 750 and see how it goes! Will post results so if others are having the same issue its helpful! Thanks so much xx

Ok, sounds great, keep me posted! Also: are you baking the entire loaf? Or splitting that amount of dough into two loaves?

I can’t get over how incredible it is to get feedback from a real person, sometimes just reading about it leaves you with more questions! Thank you! Okay so yes I am dividing the dough in half to bake two loaves. I baked this morning. I kept the recipe the same but did bulk ferment till it was exactly 50% bigger, then I put it in the fridge overnight and then shaped when it was cold and then proved and baked it, I didn’t do a cold prove. A few things happened, the one is that the bread burst its slashes during oven spring and I am wondering if it’s because I should have made the prove longer to account for the fact that it was still cold from the fridge when the prove started (or maybe waited till it was room temp before shaping and starting the prove?) Then the other thing is that it’s still gummy inside. So I thought I would just post my method because its maybe a but unconventional and maybe that’s what the problem is! So I shape my loaf and then I put it directly into an oiled Romertopf, I don’t have proving baskets. (I don’t soak the Romertopf in water) I leave it in the Romertopf on the kitchen counter to prove for about 2.5 hours then I preheat my oven to 260C (500), once it’s at temp I turn it down to 220C (428) put the Romertopf into the oven with the lid on for 30 mins, then off comes the lid for another approx 40 mins. My crust is beautiful, if not a tiny bit tough but the crumb is a bit gummy and it does turn back to dough when you squish it. I have never gotten a higher temp read than 70C (158) on the inside of the loaf as it comes out of the oven, no matter how long I cook it for. So I feel like I have maybe had a bit of a lightbulb moment here, maybe it’s the way I am baking it rather than the recipe!? THANK YOU! Alila

Hi! OK, I’d really love you to try doing a 24-hour cold proof after the dough is shaped into a batard or round. Then try your romertopf method, but bake the cold dough — don’t do a room temperature proof. After 24 hours, put the cold dough in the romertopf, slash it, cover it, then transfer it to the oven to bake.

It’s very interesting to me that you can’t get a higher dough temperature… not sure how to advise, bc if you’re baking a loaf for 70 minutes, it definitely should be over 205ºF or so.

Yeah, one thing you could do is try a completely different recipe, like a sourdough focaccia or a toasting bread that doesn’t require a heavy, lidded baking vessel.

Good luck!

I have a pretty mature starter that makes a failsafe low-maintenance loaf every time.

I wanted to give your methods a try, but I have a question – my dough is always sticky. Usually, when I turn it out after bulking I’ve always had to oil my hands and this negates the stickiness, but in your videos it looks like you just have your ‘raw’ hands, yet the dough doesn’t seem to stick.

(I just tried my stretch and fold 30 mins in and had loads stuck to my hands once done.) I use a very strong plain white flour (and very hard tap water) – in case that makes any difference.

I’m almost scared to deviate too far from what I know… 😟

Hi Ray! Sticky is OK. It’s a total lack of strength and elasticity that is not OK. When you turn the dough out, if it is a puddle, that’s when the dough is unsalvageable, but that doesn’t sound like what’s happening to you.

A few thoughts: use wet hands when you do the stretches and folds.

Regarding shaping, I just prefer not using anything — flour, water, oil — but that’s just me. You definitely can use a little bit of flour while you are shaping, which might help. And if you are happy with oil on your hands, keep doing that. Also, I do use my bench scraper a lot, and I handle the dough minimally with my hands — after a few moves with the bench scraper, when the dough has developed some tension, it’s easier to use your hands — it won’t stick as much then.

Hope that helps! Let me know if there is anything else.

Great, thanks for the feedback!

Yep, I’ve only had a ‘puddle’ of dough once or twice – and that was when I knew I’d left it too long.

If sticky dough is ok, then whew 😌. I’ll give the ‘slightly wet hands’ method a try – certainly a lot easier than the oiled approach! And yes – a good (better) bench scraper is on my shopping list – I’m using a plastic one that is nice and flexible, but starting to show signs of ageing…

Ok, great, keep me posted!

Really enjoyed reading your very good article. So helpful. Also every comment!

I get good and not so good results with my Sourdough but never really bad but by reading I always learn some new tips.

I always bake my bread from a cold start. Remove loaf from the fridge, into the pot and into the oven after slashing, then set the temperature and time. I get good oven spring mostly.

I use an enamel casserole pan with lid. Would I get better results with a cast iron pan?

My dough is sometimes a bit wet so do play around with the water addition.

It’s a very ‘fun’ time baking bread and I haven’t purchased bread since ‘lockdown’ last year. :)))

So great to hear this, Mary!

Regarding your baking method and the enamel casserole pan with lid, if you’re getting good results, I would just keep doing what you are doing. From what I have learned, I think if you are using an enamel casserole pan with lid, the cold pan, cold oven method works great. With cast iron, I have better results with a hot pan, hot oven.

If i bulk ferment on the bench then fridge overnight and it has doubled before I fridge, do I have to let it come to room temp before shaping?

Not necessarily, but I always recommend to shape preferably when the dough is at room temperature and then to follow the shaping with a 24-hour cold proof.

I’m reading this and it’s a Wonderful explanation! You say the starter should double in four to six hours. Is that dependent on the temperature of your room. My starter doubled in six last summer when even with ac on my kitchen was 73 degrees. But this winter I noticed it takes more like 8 hours to double when room temperature is between 68-70. I feed my starter with water that is around 88 degrees. Curious your opinion.

Hi Robin! I should edit the post … and I will soon. Doubling in 6 hours is great and 8 in the winter is fine, too — yes, the time is definitely dependent on room temperature, environment, and season.

Hello! I’ve followed your advice and I’m getting just the most beautiful bread except that the bread is still bursting its slits/ underneath! I’m doing a 24 hour cold prove and as per your advice I don’t do a room temp prove after that it just goes straight from the fridge, gets its slits and then goes into a hot hot oven. Any advice on how to solve the bursting? I do pretty deep slits, and sometimes it bursts on the top and sometimes it bursts underneath, not sure if that’s relevant..? Thanks so much!

Just had a thought, should I be letting it come to room temp first before I do the shaping and the bench rest? Then shape, bench rest and refrigerate for 24 hrs?

Thanks!

Hi Alila!

Great to hear you are getting good results!

Regarding the bursting, I don’t think letting the dough come to room temperature before shaping and proofing will make a difference, but I am all about experimenting, so you could definitely give that a try.

My gut is that it has to do with the shaping itself and if you are creating enough tension.

But I also wonder if you are potentially letting the bulk fermentation go too long or if you potentially could reduce the water slightly.

Do you live in a humid environment? And roughly how many hours is the bulk fermentation? And are you using a straight-sided vessel for the bulk?

Hey!

Thanks for the reply. I use 70% hydration not a humid environment but it is winter here now. I really don’t think I’m letting the bulk go too long. I am using a straight sided vessel and I bulk ferment till its grown between 50 and 75%. Then I put it in the fridge. Then I take it out, do my shaping – as per your instructions- then I put it in my loaf pan and put it back into the fridge for a 24 hour cold prove. It’s not bursting a lot, but it is opening a bit… happy to experiment more, just wanted to ask in case there was something obvious like letting it come to room temp so that the 40 min (in winter) bench rest is done at room temp not with cold dough…

Ok, well, it sounds as though you are doing everything right. Last question: what type of flour are you using?

My dough was in frig for 5 days it had a nice feel it had lots of Bubel and while working on it was sticky please tell me my mistake

Still got answer why dough is sticky

Hi Sylvia,

Your dough can be sticky for many reasons. It sounds as though it perhaps over-fermented. 5 days is a long time in the fridge. Next time, I would try for a 24-48 hour proof.

Hi

Absolutely love your method I use Shipton mill flour in UK and your hydration makes it well and not well risen. I had been using a 60percent hydration which was perfect but very drawn out. Do you think I could adapt your recipe to that ?

What would you suggest please

Thank you

Trish

Hi Trish, is Shipton mill flour stone milled or roller milled? Do you know the protein content?

These are the two simple sourdough bread recipes I recommend:

Simple Sourdough Bread, Step by Step

Simple Sourdough Bread, Whole Wheat-ish

Just to be clear, if my starter over ferments or more than doubles in size, its ok you use as long as I stretch and fold for 2 hours? I am still having trouble getting bigger air pockets in my bread. could this be part of the problem? Is there a difference from using tepid and warm water?

Hi Carol!

So, it’s OK for your starter to double or even tripled in volume as long as it’s still on “the up” as in it hasn’t collapsed and has started to look very thin with lots of tiny bubbles and has a very acidic smell.

The stretches and folds have nothing to do with your starter. Once your starter is added to the dough, the stretches and folds will build strength in the dough. If your starter is not bubbly and active when you add it to your dough, the stretches and folds won’t help that.

I always use room temperature water, but using tepid or lukewarm water is totally fine. The water temperature won’t affect the air pockets.

My biggest tips for getting more air pockets are:

1. Use a scale to measure.

2. Make sure you are using your starter at its peak. And make sure it’s very active — as in doubling or tripling in volume within 4 to 8 hours of feeding it.

3. Ending the bulk fermentation at 50-75% increase in volume.

4. Shaping like a batard as in the video included above.

5. At least a 24-hour cold-proof in the fridge.

Hi Ali

Thank you, thank you for your clear & concise webpages, for not using 100 words when 10 will do, for not telling me your life story or starting every sentence with the word “so”.

I’ve baked my own bread for over 40 years and only recently thought about trying sour dough. Numerous visits to other websites left me quite dispirited, they all seemed to tell half a story and unecessarily mystefied the process. Your recipe gave me all the information I needed to give it a go with confidence.

Dark rye flour and water for the starter – wow, bang on first time, really muscular starter. I think I let it ferment for slightly too long because the first rise was disappointing but restarted the starter and then mixed some of it into the dough with a mixer and dough hook. It worked a treat and keeping the dough in the fridge for the second rise was a real revelation, not only in the resulting loaf but also it because it giave the flexiblity of time to choose when to bake.

I was very happy with this my first attempt, far exceeded my expectations. This is all due to your excellent recipe and tutorial, thank you again.

Edward

So nice to hear this, Edward. Thanks so much for writing. And nice work mixing in more starter after the first rise — brilliant! What’s fun about sourdough is that every batch teaches you something, and you get better with each successive bake. And I agree: I love the flexibility of having a loaf in the fridge that I can bake off when needed. Anyway, thanks again for writing, and thank you for your kind words 🙂 🙂 🙂

I had signed up for your email class for sourdough. I see you have print options for the recipes but what about the actual information? I find the ads really distracting and would like to be able to print off the information so I can read it without all the ads popping up….. is there a pdf link?

Hi Alexandra,

Thank you so much for your amazing instructions! One question I had was, when you feed twice before using the starter, do you refrigerate the starter in between feeds if your first feed is in the evening or do you leave it on the counter overnight?

Thank you for your advice! My family has really enjoyed your recipes, from the sourdough breads and pizzas, to the discard pancakes and tortillas.

Sincerely,

Kim

Hi Kim!

Apologies for the delay here. I leave the starter at room temperature when I feed it twice before using. So, I feed it at night, let it sit on the counter, feed it in the morning, and again let it sit on the counter.

So nice to hear all of this 🙂 🙂 🙂 Thank you for your kind words 💕💕💕💕

Hi Ali!

I’ve been doing sourdough for a bit now and your recipe has always been my go to!! As of late though my starter hasn’t been rising so much and does not seem to double in size. It still passes the float test and I’ve still used it to make bread and the bread turns out fine. Is there a reason as to why it won’t double in size? I’ve been thinking maybe it’s too cold in my house but not sure. What do you think?

Thanks in advance!!

Hi Victor! Are you being aggressive with how much starter you are discarding before a feeding? You should really be discarding most of it, leaving only a tablespoon or two behind before feeding it with fresh flour and water. Try buying some organic flour or even some freshly milled, stone-milled flour, and use a mix of this flour with your bread flour or all-purpose flour — a 50/50 blend.

thank you! i will give it a try!

Hi Ali, I’ve made this recipe twice with very good success. I am cold fermenting 2 more at this time. I am fortunate to have received a proofer as a gift and have used it thus far. My problem is my dough is very sticky. I do add humidity in the proofer. Should I do a dry rise instead? I do think I may have overproofed also because the dough doubled. It rises so slowly in the proofer until the last 30 min. and then it explodes!

Also, can I bake the loaves in a clay baker? Thanks for your help!

I don’t think the humidity in the proofer itself is making the dough sticky. It’s likely due to over-fermenting during the bulk fermentation or using too much water.

Are you using a scale to measure? Do you live in a humid environment? What type of flour are you using?

Yes to using a clay baker!

Yes, I use a scale for all ingredients. I use KA bread flour. It is not humid here, about 70 degrees. I set the proofer to 78-79 with a water dish so I suppose the proofer environment is humid but the kitchen is not. I guess I should watch the first proof more carefully so it doesn’t go above 50% rise and maybe lower the proofer temp?

This was my first sourdough ever and it is delicious none-the-less! I love your recipe and will continue to use it until I get everything right! Thank you for this incredible recipe!

Great to hear all of this, Carol!

I think lowering the temperature of the proofer is a great idea. I always bulk ferment at room temperature and while it does make the process longer, the risk of over-fermenting is low. And going about the 50% mark is fine — I have done so on many occasion — but for some people, sticking to that mark makes all the difference.

Keep me posted on your trials!

If I feed my starter with rye flour, how much should I use? What’s the ratio? Should I use a mix of all purpose and rye or just rye? Thanks!

Hi Geetha,

I always do equal parts by weight flour and water regardless of what flour I am using. You can use 100% rye or a mix. Keep in mind that using a rye starter will affect the gluten structure of your dough. Rye does not have has much gluten and therefore you might find your loaves to be denser as a result.

How would you salvage a too wet dough? I followed the 75% hydration, but the dough (even with 4 stretch and fold) is very wet and not elasticky. Can it be salvaged? Still try to shape and leave for cold fermentation? What do you suggest?

Hi Ann! I might try baking it in a loaf pan or 9×13-inch pan to make more of a focaccia like loaf. Which recipe did you follow? And did you use a scale? And do you live in a humid environment? Finally: what type of flour?

do you think this dough would also be good for calzones? fun to make with the grand kids

Hi Phyllis! I’m not sure which recipe you are referring to, but this Simple Sourdough Pizza Crust recipe would be great for calzones.

I so appreciate this blog post, thank you! It’s helped answer so many questions that I couldn’t find answers to anywhere else.

However, I have a question about sourdough starters (as a noob!) that I have yet to find anywhere, and I’m hoping you can help. I’ve had a rough go trying to figure out my sourdough starter but it’s finally becoming active. What I can’t figure out is this: so in the beginning I would have around 100 grams of sourdough starter, would add 100 grams of flour and 100 grams of water. It wouldn’t grow much so it would end up being around 200 grams the next day when I went to feed it. So I would discard half and be left with 100 grams of starter and would continue the 1:1:1 ratio by adding 100 grams of flour and 100 grams of water.

Now, each day the sourdough starter is a different weight. Some days it’s up to 400 grams – on those days, discarding half would make it so that I’m left with 200 grams of sourdough starter. So I’m assuming on those days I feed it 200 grams of flour and 200 grams of water to continue with the 1:1:1 ratio? I’m just wondering if this will slow down the activity by feeding it a different amount each day. On the other hand, every recipe I’ve seen has said something like “discard half and then add 100 grams of flour and 100 grams of water to feed it” but if you have 500 grams of sourdough starter at that point, discarding half would leave you with 250 grams of sourdough starter. Therefore, feeding it with only 100 grams of flour and 100 grams of water would make it uneven and no longer a 1:1:1 ratio. Is it normal to feed it a different amount each day? Thanks in advance!

Hi Sarah! OK, I want you to forget the 1:1:1 advice. Next time you go to feed your starter, discard most of it: hold the jar over the trash can (unless you are saving the discard for some other use) and scrape out most of leaving just 2 tablespoons or so behind. It will seem scary to leave only a tiny bit behind, but I’m telling you this is where people go wrong — they are not aggressive enough with how much starter they discard. Then add flour and water at a 1:1 ratio. Doesn’t matter how much: 50 grams each, 75 grams each, 100 grams each. Let the starter rise for 24 hours. Then repeat. If after the second feeding you see some good activity, repeat the process before you go to bed and see how it looks in the morning.

In short: I never weigh how much starter is left in my jar after I discard the bulk of it. I always weigh the flour and water that I feed to it, and I always make sure I feed at a one-to-one ratio of flour and water.

Let me know if that helps!

Hi! I am having so much fun making your sourdough, my husband’s favorite bread. I only have one consistent problem, the bottom gets very dark, almost burned, but the rest is fine. I have a great oven and use the proper dutch oven…please help.

Hi Carol! Great to hear this. Also, apologies for the delay here … I’ve been out of the country.

Here are some thoughts (which, for future reference, you can find in the post above):

If you are using a preheated Dutch oven, consider lowering the temperature.

Before you make changes to the temperature, however, next time you bake, check the dough after 30 minutes. If the dough is browning too much on the bottom, you know that it’s happening during these first 30 minutes, in which case, you should lower the temperature from the start. Decrease it by 25ºF.

If the dough is not browning, then you know the burning is happening during the last 15-20 minutes of baking, in which case you could remove the loaf from the pot after 30 minutes and bake it on a sheet pan.

Another option: place your Dutch oven on two sheet pans. I do this with challah to prevent the bottom from burning. The extra layer of sheet pans will prevent the bottom of your sourdough from burning, too.

Another option: place your Dutch oven on a broiling pan.

Finally: Use rice flour for dusting — it makes all the difference. It does not burn the way wheat flour does. It also doesn’t coat the loaves with an unpleasant raw flour taste. One bag will last you a long time.

Hey Ali! I’ve been on a sourdough kick for the last couple of months. Your post cleared some things up for me – yay! And thanks for the Open Crumb Mastery suggestion. I did buy it, but just a heads up. Your link sends you to a gambling site.I went on a hunt for his book and found it through his Instagram account (which is pretty amazing). Here’s the link to purchase the book. Hope all is well! Heading to Rhinebeck for the Sheep and Wool Festival this week (from Philly).

Thank you, Lisa! I updated the links. So weird about the gambling site. So glad you got the book. It’s wonderful!

Hi! I cold proofed my dough for approximately 36 hours. I took it out to find a dry, crumbly, brick. Do I start over or can it be salvaged? I’m about to give up on baking my own sourdough! Proving difficult!

It’s likely unsalvageable at this point. Next time, tuck it into an airtight bag — even a produce bag from the grocery store — to prevent it from drying out.

Hi! I am fairly new to sourdough & was hoping for some clarification on using the fridge to your benefit!

So, say I mixed my dough & finished the folds around 5pm. At 10pm my dough didn’t appear 50% increased or have any bubbles on the surface. So to throw it in the fridge, should it be covered tightly with plastic wrap or just draped with a kitchen towel? And when I remove it in the morning, should I make sure it comes to room temperature before I do any touching/shaping & will it take a good amount of time to begin bulk fermentation again?

Thanks in advance!

Hi! Definitely cover the bowl with tightly with plastic wrap — this will prevent a crust from forming. When you remove it from the fridge, I would let it rest at room temperature, and I woudn’t touch it until you see it has increased in volume by 50-75%. It may take a while for the bulk fermentation to complete due to the cold temp of the dough coupled with the time of year.

Hi Ali

I’ve been struggling to understand how long to bulk ferment. My fridge is cold and my shaped dough never rises at all after being placed in the fridge. From everything I’ve read it’s not supposed to, or at least not once the dough drops to 4°C or less. Can you explain why if I am going to cold proof after my bulk ferment I should let it rise less than if I’m not?

Hi Allison,

It is true that sourdough will not rise much in the fridge due to the cold temperature. That said, fermentation and enzymatic reactions are still happening once the dough is in the fridge.

If you have a straight-sided vessel, try this experiment: let the dough rise until it has doubled during the bulk fermentation, then proceed with a cold ferment. See how it turns out. On a separate batch of dough, let the dough rise until it increases in volume by 75%, then proceed with a cold ferment.

See which one you like better, then adjust your method from there.

HI. I am right now bulk proofing a sandwich sourdough recipe for 2 loaves. It called for 8 cups flour, and said to start with 7. I measure in grams; my flour comes in at 120 gr per cup. (King Arthur). My dough was very soft, and I ended up using ~8.25 cups (1000 grams) just to get it to a “reasonable consistency-but not what I’m used to. Only after I started the bulk proof did I notice the recipe called for 1200 gr of flour (150 gr per cup). Even 7 cups worth at this weight would be 1050 gr.

Is there any way I can save this dough? It’s a sandwich loaf; can I knead in more flour before putting the dough into the pans? This is a 2 loaf recipe.

Thanks for your thoughts!

Alice